Reconceptualizing Home in Times of Precarity

BY EMMA TALLON

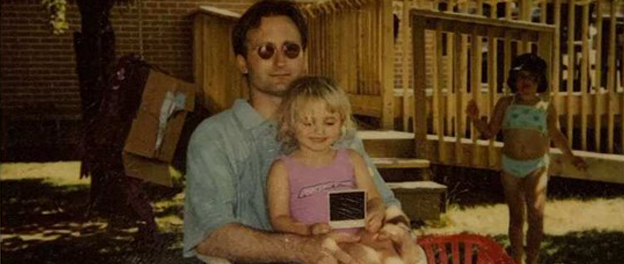

Photo from the author’s family archive.

I have found myself at 3:00 in the afternoon every day standing on my back porch staring at my neighbour’s garden windmill. It is nothing special as far as windmills go. It is rainbow and occasionally, if the weather permits, I watch it spin. Rain or shine, I am there.

The windmill takes me back to my childhood; times spent gardening and walking along the creek in my grandmother’s backyard. The colours belt out innocence and urge me to crawl inside—like a baby returning to its mother’s womb. But, even more so, the windmill ignites a feeling of home within me. Although anthropologists have traditionally referred to home as a physical space, as a dwelling, as ‘the material circumstances of life,’ in reality, the meaning becomes fragmented (Morgan, 1881; Bourdieu, 1976). It is often seen as a site of kinship, collectivity, and ritual. Yet, these definitions do not explain why I feel myself taken back home every time I stare at my neighbour’s windmill. This is because, for me, the notion of ‘home’ does not imply physicality, nor is it a place I can always return to in times of trouble. At this moment in my life, home denotes precarity.

Kathleen Stewart (2012) demonstrates the role of precarity in ethnographic writing, as she states that, “Precarity’s forms are compositional and decompositional. They magnetize attachments, tempos, materialities, and states of being […] The writing itself attunes us to how things are hanging together or falling apart” (Stewart; 2012, 542). Over the winter break, I was tasked with clearing out my Dad and I’s home—a place that I referred to as my physical home for most of my youth and young-adult life. However, without my Dad, the home no longer felt like a coming together, but, as Stewart explores, a falling apart. My Dad passed away from a fleeting battle with cancer in August. In an attempt to distract myself from the unknowingness of my life at this present time, I decided to turn my experience of packing into an ethnographic pursuit. Was it a desire for some degree of closure? Or, a desire to understand my current state of unknowing? Perhaps, it was simply a tendency towards emotional masochism? Who knows, honestly. All I know is that in times of precarity, it is only natural to search for answers, for a coming together.

To refer back to Stewart, since the passing of my Dad, I have been in a peculiar ‘state of being’ (Stewart; 2012: 542). I have been told by those around me that I seem clouded, distracted, or, my personal favourites, tired and stressed. Yet, in actuality, I have been confronted not only with my own vulnerability without my Dad by my side, but with the precarity of home when one thinks of it solely in terms of its structural makeup. I have been exposed to home’s fragility: something that can be made, but also unmade, held together, or left to fall apart.

Home, for my Dad and I, has always been an interesting point of discussion. Not only have we lived in an abandoned Christian boy’s private school (urinals and all), a historic, yet deeply haunted 1834 stone home that was frequently ‘visited’ by a piano composer, but also a farmhouse that, although charming, lacked proper heating and led my Dad and I to eat our spaghetti dinners in our snowsuits. Although to an outside observer, our home circumstances may have seemed precarious, they could not have been farther from that. We were always comfortable. My Dad instilled in me from day one that I would always be safe. No matter where we lived, I always had my own room that was fully stocked with Hudson Bay blankets, vinyl records, vintage licence plates hanging on the wall, and one of my Dad’s many Persian rugs that he always said ‘tied a room together’ (it was not until I watched The Big Lebowski while in university that I understood the reference my Dad was making). For us, home did not really matter where we lived, though my Dad had quite a creative mind and was always in the mood for a new project. Above all, what mattered to us was that we were always together. As Stewart states, precarity can also be a ‘hanging together’ (Stewart; 2012: 542). The precarious nature of our life hung together beautifully like the Simon and Garfunkel ‘Wednesday Morning, 3AM’ and Led Zeppelin II albums hanging on the wall of my teenage bedroom.

Edward Casey (2001) explores the making of a place and the impact that process has on human consciousness, as he states, “[P]laces require human agents to become primary places” (Casey; 2001: 405). A home is more than a structure made up of four walls and a roof. It is, as Casey posits, a marker of one’s personal identity. Home and one’s identity go hand in hand, as “there is no place without self; and no self without place” (Casey; 2001: 406). Casey gets at a very important point here, and something that I have been struggling to come to terms with. For most of my life, my identity was tied not only to my Dad, but to our home. The environment that my Dad shaped for me has made me who I am today. It explains why I feel a sense of ‘at home’ in chaos and could never, under any circumstances, live in a ‘magazine-esque’ home. It explains my desire to pursue a more creative career path, as well as prioritize experience over financial comfort. It explains my love for adventure. Above all, it explains my ability, akin to my Dad, to see beauty in things people would normally look past without a second thought.

You can sense my discomfort in trying to decipher who I am in lieu of losing the two key markers of my identity. In an attempt to reconcile these feelings, I have allowed myself to fall into a realm of ‘negative capability’—explaining my previously-mentioned state of cloudiness. John Keats (1817) describes negative capability as a specific state where one is “capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” I am working on finding comfort not only in the precarity of home, but in my own precarity of self. Casey’s (2001) work provides useful information in this regard. He argues that there is credence in precarity. For, in times of trouble, of falling apart, one’s identity and mindset come out changed. He states, “the more places are thinned out, the more, not less, may selves be led to seek out thick places in which their own personal enrichment can flourish” (Casey; 2001: 408). The precarious nature of my home has urged me to recognize that home is not a physical space. Home is a yearning. It explains why I feel myself clinging to anything that remotely reminds me of home—hence my deep-seeded need to stare blankly at my neighbour’s window every afternoon at 3:00 (yes, like clockwork). It explains why for four months following my Dad’s passing, I had to carry his business card in my jean pocket. It explains why, if you reach into the inner pocket of my bag, you will find a rock I collected on one of my Dad and I’s many camping adventures. It explains why I can only sleep through the night if I have one of my Dad’s perfectly worn-out t-shirts with me. It explains why I feel my heart skip a beat whenever a friend or family member says that I resemble my Dad, particularly my sky-blue eyes that we share.

While I may have lost my physical signifiers of home, I carry them within me wherever I go.

“But I, being poor, have only my dreams;

I have spread my dreams under your feet;

Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.”

W.B. Yeats, The Wild Among the Reeds

References

Bourdieu, P. 1976. Marriage strategies as strategies of social reproduction.” In Family and society (eds) R. Forster & O. Ranum, 117-44. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Casey, Edward (2001). “Body, Self, and Landscape: A Geophilosophical Inquiry into the Place-

World,” in P.C. Adams, S. Hoelcher and K.E. Till (eds) Textures of Place: Exploring Humanist Geographies. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, p. 403-425.

Keats, John (1899). The Complete Poetical Works and Letters of John Keats, Cambridge Edition. Houghton, Mifflin and Company.

Morgan, Lewis Henry, Geographical and Geological Survey of the Rocky Mountain Region (U.S.), & Smithsonian Institution. (1881). Houses and house-life of the American aborigines. Washington: G.P.O.

Stewart, Kathleen (2012). “Precarity’s Forms.” Cultural Anthropology, 27, 3: 518–525.